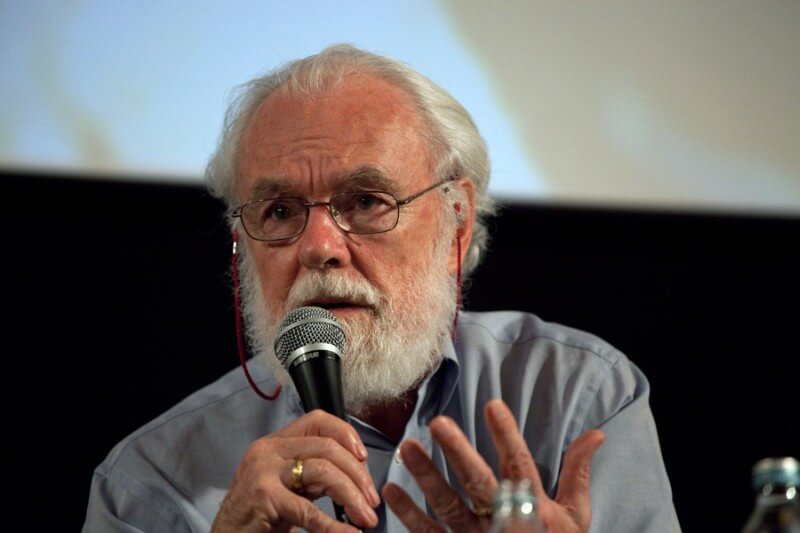

Luis C. Córdova[1].

Abstract: In Latin America and the Caribbean, security has emerged as the focal point of government action. A deadly combination of corruption, crime, and violence has ignited the region, spreading bewilderment and fear throughout society. The state response is varied but generally follows two paths: the depoliticization of the problem and the militarization of security. The public debate surrounding these responses appears to be stagnant, driven more by a lack of ideas than by censorship. Security has pushed conflict out of the political debate. Is there an alternative? To challenge the meaning of security policies, two issues must be addressed: how the foundation of the idea of security underpins the emergence of a “democratic despotism” and how to deactivate the affective structure of fear that fuels a “warrior worldview” among state agents and paranoia among citizens. Exploring these questions reveals that security is a political field where the struggle for power shapes its contours.

![]() Download: Security as a Political Field: A Conceptual Approach

Download: Security as a Political Field: A Conceptual Approach

After a wave of criminal violence that shook Ecuador at the beginning of the year, President Daniel Noboa signed an executive decree acknowledging the existence of an internal armed conflict and designating 22 criminal groups as terrorist organizations. Although unusual, the declaration of “internal war” was not naive. It facilitated the country’s total and permanent militarization. To endorse it, the president promoted a referendum and popular consultation, with questions centered around the militarized discourse of security. On April 21, Ecuadorians went to the polls and approved 9 out of the 11 questions. Four months later, the issues that led to the declaration of war remain unresolved, but society has normalized the military presence on the streets and criminal violence in the news. .

In Latin America and the Caribbean, security has emerged as the focal point of government action. A deadly combination of corruption, crime, and violence has ignited the region, spreading bewilderment and fear throughout society. The state response is varied but generally follows two paths: the depoliticization of the problem and the militarization of security. The public debate surrounding these responses appears to be stagnant, driven more by a lack of ideas than by censorship. Security has pushed conflict out of the political debate.

We are witnessing a new era of “democratic despotism” (Tocqueville, 1957). In the name of order—as if it were the supreme value of democracy—the rulers have given free rein to military power. Mexico is a paradigmatic case (see Mexico United Against Crime, 2024). The sense of order defended by current militarism is not very different from the one exalted during the military dictatorships sponsored by the United States during the Cold War. Progress, social peace, and freedom are among the labels used in the speeches of the new despots: Nayib Bukele (El Salvador,) Javier Milei (Argentina,) or Daniel Noboa (Ecuador). Today, the distinction lies in the deliberate avoidance of shattering the democratic façade. Democracy has become a mere shell.

As Illouz (2024) warned, “politics is loaded with affective structures.” Deciphering the emotions that sustain social structures is a preliminary step towards politically articulating a response. In contemporary society, fear and distrust shape affections and pave the way for authoritarianism. Europe and North America experienced this during the “war on terror” following the September 11, 2001 attacks. Latin America and the Caribbean have been living it for fifty years in the “war on drugs.” Prison massacres, targeted assassinations, and disappearances are part of this nomenclature of horror that is shaping a subjectivity throughout Latin America conducive to militarist responses.

Is there an alternative? To challenge the meaning of security policies, two issues must be addressed: how the foundation of the idea of security underpins the emergence of a “democratic despotism,” and how to deactivate the affective structure of fear that fuels a “warrior worldview”[2] among state agents and paranoia among citizens. Exploring these questions reveals that security is a political field the contours of which are shaped by the struggle for power.

Thomas Hobbes’ political philosophy serves as the foundation for the sense of contemporary militarism in the region. . The core of his approach is that, in the face of an existential threat to state security, there is no alternative but a Leviathan. Thus, in the face of existential threats (narcoterrorism or organized crime), calling the military to restore order by force becomes an “existential necessity” (Neal, 2019). It is the “representation of order” embodied in the idea of the State, that supports “heavy-handed” policies[3].

But this “representation of order” lacks empirical support when the modern State is viewed from a historical perspective. In Europe, for example, Tilly’s work (1985) demonstrated that war, resource extraction, and capital accumulation interacted to make state-building possible. In this process, the distinction between “legitimate” and “illegitimate” violence was a blurred line, as criminal and proto-state actors competed for authority through force, attempting to monopolize the “protection business.”

In Latin America and the Caribbean, history has been somewhat different. State-formation was late (from the 19th century onwards), and state-building depended more on the incorporation of the peripheries into the market and their socio-political transformation than on the waging of war (Mazzuca, 2021.) Most countries remained patrimonialist states led by oligarchs or caudillos well into the twentieth century. The Somoza dynasty in Nicaragua is an eloquent example. For this reason, armed actors and criminal violence are not systemic failures for the region but “characteristics of a highly unequal political system that continues to struggle with legacies of exclusion and authoritarianism” (Arias, 2017: 8).

Security as a political field rejects this metaphysics of order and questions the idealized representation of the State. Following Roberto Esposito’s hermeneutic proposal (2012), an “impolitical” view of security is advocated here; that is, a liminal approach that frees it from any undue assessment and recovers its political facticity: the conflict for power. In this sense, security ceases to be the substance that justifies the existence of police and military forces and becomes a field of dispute in which political subjects struggle to define their contours in a relational and always incomplete manner.

The political field of security is configured through the interaction of state, paramilitary, and criminal actors who organize violence in society. These actors sometimes rival each other and sometimes cooperate because they are the only ones who can manage the protection business, either in exchange for a tax or as a means of extortion. From this perspective, state-organized violence does not have inherent value but is significant only to the extent that it is democratically regulated. It is the democratic rules that limit the State’s coercive power that make the difference.

If “democratic despotism” occurs today, it is because the meaning of democracy has been disrupted, stripping it of its technical content. Contemporary despots reject any democratic rule that limits State-organized violence (Police, Armed Forces, and Intelligence services.) Under the pretext of neutralizing threats, they demand greater power, operating amid opacity and whim. Paradoxically, they do all this in the name of democracy. The result is a Leviathan that undermines the very foundations of the legitimacy that supports it. Without institutional constraints, military power and criminal power ultimately drown society in blood. Somalia or Haiti are the proof of this.

In this logic of security, politics is a byproduct of war. Politics becomes war by other means. Therefore, there is no place for difference, discrepancy, or conflict. The lives of citizens depend on the deaths of narco-terrorists and all their allies and accomplices. A permanent state of war is inaugurated that restricts democracy to the point of starvation.

There is no doubt that citizen protection is a fundamental public good necessary for the exercise of other rights. Without minimum conditions of individual security, children and adolescents would not be able to attend school. For this reason, protection is a fundamental task of a democratic political community (González, 2020). In theory, this political community is equipped with a state apparatus responsible for guaranteeing it through the monopoly of the use of force. In practice, this is not the case.

In highly unequal societies, such as those in Latin America, the coercive apparatus of the state distributes protection and repression based on the existing socio-economic structure.

In zones where inequalities are chronic, it is likely that the state enforces more repression than protection, thereby preserving these asymmetries. Chiapas, the poorest state in Mexico, is a heartbreaking example of this dynamic: while the state represses nonconformists, criminal groups sell protection in a well-established criminal governance scheme (see Ferri et al., 2024.)

It all depends on how political economies are configured locally: the agreements established by economic actors (formal, informal, and illicit) and government authorities to define protection priorities or repression objectives; and the types of actors involved in providing security, such as police, military, intelligence services, municipal agents, private security guards, or paramilitary structures.

From this point of view, illegal economies allow the reproduction of capital by extracting revenue from the State (through corruption in public procurement), from natural resources (through illegal mining or trafficking in species), and from the population under their control (through extortion and kidnappings), as required. Criminal capital has always been functional to capitalism, and organized crime has been a co-participant in the construction of the modern State (Andreas, 2013; Mandić, 2021; Paley, 2014; Tilly, 1985.)

Conceiving security as a political field requires a dynamic stance against the official theses. Above all, it is essential not to reproduce the narratives of fear and distrust that weave the “feeling rules” (Flam, 2005) of militarization. This is where the Left tends to lose ground quickly. Without a programmatic compass to dispute the political field of security, they reproduce the narratives that flood the “common sense” of society: “more resources for the police,” “more military on the streets,” and “more control at the borders.” This establishes a culture of violence that is capitalized on by far-right o radical right-wing sectors.

Therefore, it is urgent to design an emotional strategy for the political field of security. However, this will only be possible by articulating a critical discourse on security— one that exposes the ideological trap of “presenteeism,” which cultivates fear in society. In other words, a discourse that reintegrates the future into political life to transform it democratically (White, 2024.)

Organized crime violence is a long-term challenge that requires far-sighted strategies. But the “heavy-handed” policies and militarization are immediate, often desperate responses. As foreseen by Innerarity (2020: 370) “there is no collective intelligence if societies do not manage to reasonably govern their future. The future is a construction that must be anticipated with some coherence. […] When the time horizon narrows and only the most immediate interests are considered, it is very difficult to prevent things from evolving catastrophically.”

The idea of security as a political field may be the battering ram the Left needs to reclaim the initiative and develop a political agenda with a future. An agenda in which “the idea of a democratic form of life” (Honneth, 2017.) there is room. An agenda in which the strategic horizon is not war, but life.

Works cited:

Albarracín, J. (2023.) Crimen Organizado en América Latina (Organized Crime in Latin America.)

Andreas, Peter. (2013.) Smuggler Nation. How illicit trade made America. Oxford University Press.

Arias, E. D. (2017.) Criminal Enterprises and Governance in Latin America and the Caribbean. Cambridge University Press.

Esposito, R. (2012.) Diez pensamientos acerca de la política (Ten Thoughts about Politics.) Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Ferri, P., Santos, A., & Guillén, B. (2024, April 13.) Chiapas, territorio tomado (Chiapas, taken territory.) El País. https://elpais.com/mexico/2024-04-14/chiapas-territorio-tomado.html

Flam, H. (2005). Emotions’ map. A research agenda. In H. Flam & D. King (Eds.), Emotions and Social Movements. Routledge.

Gonzalez, Y. M. (2020.) Authoritarian Police in Democracy. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605320001167

John, A. (2017.) The idea of Socialism. Polity Press.

Illouz, E. (2024.) Fascismo y democracia: el gusano en la manzana (Fascism and democracy: the worm in the apple.) Nueva Sociedad, 310.

Innerarity, D. (2020.) Una teoría de la democracia compleja. Gobernar en el siglo XXI. (A Theory of Complex Democracy. Governing in the XXI Century.) Galaxia Gutemberg.

Mandić, D. (2021.) Gangsters and Other Statesmen Mafias, Separatists, and Torn States in a Globalized World. Princeton University Press.

Mazzuca, S. (2021.) Latecomer State Formation. Political Geography & Capacity Failure in Latin America. Yale University Press.

México Unidos Contra la Delincuencia (MUCD.) (2024.) El negocio de la militarización: opacidad, poder y dinero (The business of militarization: opacity, power and money.) https://www.mucd.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Negocio2.0.pdf

Neal, A. W. (2019.) Security as politics: beyond the state of exception. Edinburgh University Press Ltd.

Paley, D. (2014.) Drug War Capitalism. AK Press.

Tilly, C. (1985.) War Making and State Making as Organized Crime. In Bringing the State Back. Cambridge University Press.

Tocqueville, A. de. (1957.) La democracia en América (Democracy in America) Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Vitale, A. S. (2021.) El final del Control Policial (The End of Police Control.) Capitan Swign.

White, J. (2024.) In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea. Profile Books.

[1] Luis C. Cordova A. PhD in Political Science from the University of Salamanca. Director of the Research Program on Order, Conflict, and Violence at the Central University of Ecuador. His research focuses on political and criminal violence, civil-military relations, and foreign policy.

[2] As pointed out by Vitale (2021: 32) “police officers often see themselves as soldiers in a battle against citizens rather than as guardians of public safety.”

[3]As stated by Albarracín (2023: 10), “among [the ‘heavy-handed’ policies] we found (repressive) strategies aimed at increasing the cost and probability of punishment, such as increasing the intensity of sentences and expanding the number of activities subject to custodial punishments (thus increasing the size of the prison population), decreasing the age of criminal liability, and the militarization of public security.”