In his essays on progressivism and the progressive governments in the Andean region, Eduardo Gudynas shows us how the notion and content of democracy have changed as these regimes has developed, in the sense of a weakening of democracy as it was conceived in the tradition of the Left. The author notes an ever-greater difference between progressivism and what he calls the Classical Left in Latin America.

The title of my presentation, which was proposed to me by the event organizers, does not include this Classical Left motif. Instead, it refers to leftist political movements, and I agree with speaking in the plural, because since my arrival in Latin America almost half a century ago, I have observed a variety of tendencies that claimed to be leftist, with two main points of view standing out:

The first, with the most adherents, was a Left associated with the centers of international communism – first Moscow and later Peking and Albania, which both sought for a time to epitomize the purest Leninist spirit. For all these Communist Party variants, Leninist democratic centralism constituted the embodiment of a true democracy, and everyone believed that the most perfect democracy had been established in some far-off country, the homeland of the world’s working class.

The second tendency, represented by some prominent intellectuals, endeavored to recover the legacy of a libertarian and anti-authoritarian Karl Marx. It was a cosmopolitan Left that pursued international relations in an exchange between equals; protagonists of a New Left that had sprung from the break of certain individuals and groups with Soviet Marxism and reached full bloom in the movements of ’68. Aníbal Quijano seems to me to be a man who exemplifies this trend in Latin America.

The essential focus of this movement was to return to a Marxism undistorted by Stalinism. It was therefore necessary to re-read Marx with the help of Marxist thinkers from the first few decades of the 20th century, people like Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Korsch, Max Adler, and Antonio Gramsci, but also José Carlos Mariátegui in Latin America.

Half a century ago, José Arico and other leading intellectuals in Argentina and Mexico played a very important role by publishing the “Past and Present” books, translations of independent classical Marxist authors and of the debates in Soviet Russia prior to the triumph of Stalin, such as the proceedings of the first Communist International congresses. One book belonging to this heritage is the translation of Democracy and Socialism, a work by a heterodox German communist, Arthur Rosenberg, first published in 1938. For me, rereading this book was very useful in discussing Left movements and democracy. Many texts explain to us Marx’s theory of democracy based on his writings. Such texts include those of Hegel. Still, with the exception of the classic biography of Franz Mehring, not many authors show us Marx and Engels as fighters for democracy in their actions and statements during different periods and historical moments.

Before the revolution of 1848, Marx and Engels understood their small organization, the Communist League, as part of the great democratic movement. They defined themselves as communists and democrats, and that is how they acted: Marx as editor of the democratic periodical New Rhenish Newspaper and Engels going so far as to take part in the defensive struggles of the democrats of Southern Germany who had taken up arms against the Prussian troops. In the Manifesto of the Communist Party, they proclaimed the leading role of the proletariat in a future revolution, though it did not occur to them to separate the industrial proletariat, still a minority in most European countries, from the masses of the oppressed – workers of all kinds, peasants, and the petty bourgeoisie. The revolution against the reactionary regime of the Holy Alliance was to be a revolution by a democratic movement of the masses.

With this concept of democracy, Marx and Engels claimed the Great French Revolution as the legacy of the Left. They did not make a distinction between democracy with certain formal procedures and democratic content, as today’s learned political scientists do – democracy always implied a social transformation to improve the material conditions of the oppressed and exploited. Universal suffrage was considered the most appropriate instrument to achieve parliamentary representation, where democrats would be in the majority and could overcome the resistance of the old feudal forces and the new capitalist ones.

After the defeat of the Revolution of 1848 through coordinated intervention by the forces of the old order, this faith was lost little by little in the necessarily “democratic” results of universal suffrage. Napoleon III’s rule already knew how to use the suffrage of its subjects in plebiscites as a means to strengthen its dominion. Thus, the question arose: What political means would be fully sufficient for the democratic movement to overcome reactionary forces, and what would the characteristics of a new political order be after the victory of the proletariat and its allies?

Marx’s theory, his Critique of Political Economy [A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (German: Zur [On the] Kritik der Politischen Ökonomie)] does not offer an easy answer to questions like these. Contrary to what the preachers of a barnyard Marxism think, Marx does not give us recipes for the processes of emancipation or for the structures of a future socialist order. We owe to Marx a theory of capitalism that includes the identification of the social class capable of overcoming it, but the struggle’s methods and means could not be determined by deduction from a general theory. Accordingly, Marx began to study the actual actions of workers and their brothers-in-arms in situations of revolutionary confrontation such as occurred in the insurrectionary movement in Paris in 1871.

The Paris Commune was the result of an exceptional situation in the French capital during the war between France and Germany, after Napoleon III’s spectacular military defeat. The Emperor and his army were taken prisoner by the Germans, and a new French government had to sign peace under very harsh conditions for France. Only Paris – always much more to the Left than the rest of France and now surrounded by German troops – resisted surrender, and its National Guard, made up mostly of workers and artisans, refused to lay down arms. The national government (legitimized through nationwide elections with a majority participation of monarchical parties) had to withdraw from Paris to Versailles, leaving free rein for self-government of the capital by the Commune, which lasted a mere two months. It ended with the entrance of counterrevolutionary troops from Versailles – some of them captured soldiers freed by the Germans for this very purpose – who broke the resistance of the people of Paris in “The Bloody Week,” the last week of May 1871, unleashing a veritable massacre with around 30,000 dead.

Karl Marx, who closely watched the events in France from his exile in London, had warned his supporters in Paris against premature insurrectionary acts. Even so, a few days after the defeat of the Commune, he wrote his famous manifesto for the International on “The Civil War in France,” declaring his unconditional solidarity with the defeated. For Marx, the Commune, despite its short duration, showed the traits of a higher democracy in a number of regards that cannot be expounded upon in a brief presentation. I prefer to quote a paragraph from Engels’s prologue, written 20 years after the Commune:

“From the outset the Commune was compelled to recognize that the working class, once come to power, could not manage with the old state machine; that in order not to lose again its only just conquered supremacy, this working class must, on the one hand, do away with all the old repressive machinery previously used against it itself, and, on the other, safeguard itself against its own deputies and officials, by declaring them all, without exception, subject to recall at any moment.” (Karl Marx / Frederick Engels, Selected Works in Two Volumes, Volume I, Moscow 1955, page 461.).

This summarizes what is truly novel about the Commune without going into an analysis of its democratic measures, which obviously could not grow to maturity in the few weeks of its existence. In my opinion, Engels touches on the central problem of democracy, which is not solved by installing a republic based on universal suffrage. According to Engels, how the self-proclaimed servants of society become its lords and masters can be seen not only in hereditary monarchies, but also in democratic republics. In 1891, Engels wrote: “Nowhere do “politicians” form a more separate, powerful section of the nation than in North America. There, each of the two great parties which alternately succeed each other in power is itself in turn controlled by people who make a business of politics” (Karl Marx / Frederick Engels, Selected Works in Two Volumes, Volume I, Moscow 1955, page 461).

At the end of his prologue, Engels arrives at his famous statement:

“Of late, the Social-Democratic philistine has once more been filled with wholesome terror at the words: Dictatorship of the Proletariat. Well and good, gentlemen, do you want to know what this dictatorship looks like? Look at the Paris Commune. That was the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.” (Karl Marx / Frederick Engels, Selected Works in Two Volumes, Volume I, Moscow 1955, page 463).

This quote can serve to enhance our understanding of what the famous “dictatorship of the proletariat” means to Marx and Engels. For them, dictatorship is not a dictatorial form of political regime, but another term for class rule. Thus, the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie can take different political forms, such as a constitutional monarchy, a representative republic, Bonapartism, fascism, perhaps also progressivism, but the dictatorship of the proletariat, as the Paris Commune shows, necessarily has a democratic form; a broader, deeper democracy than a pure representative democracy. This form is indeed based on suffrage, as Marx says:

“… nothing could be more foreign to the spirit of the Commune than to supersede universal suffrage by hierarchical investiture.” (Karl Marx / Frederick Engels, Selected Works in Two Volumes, Volume I, Moscow 1955, page 499).

Nevertheless, there were various regulations to prevent delegates from straying from their bases. For example, they did not receive more pay than the average salary of a worker, they were always revocable, and they had to take on not only control duties, but also specific functions of the executive.

In the Commune as it really existed, there was no absolutely indispensable leader, nor an avant-garde party to head the process. Various tendencies and political groups coexisted in the Council of the Commune, among them the Blanquists, Proudhonists, and Bakunists, and even a few followers of Marx. The idea of a single party affirming its monopoly in a constitution, as in Cuba, is completely foreign to what the Commune was, as well as to Karl Marx’s thought.

The Paris Commune and its interpretation by Marx did not play an important role in the debates of the Second International before World War I. Engels himself, having already seen the possibility that pure democracy could be an instrument of the bourgeoisie – that is, undemocratic – reckoned shortly before his death that the Social Democratic Party (remember that this was what Marxists were called at the time) could come to power by gradually increasing its vote in the general elections. It was only in 1917 that Lenin, in his work State and Revolution, arrived at a reconstruction of Marx’s authentic thinking regarding the Paris Commune by linking it with the particularities of the Russian Revolution. According to him, the Soviets – having already figured in the Russian Revolution of 1905 and again after February 1917 – freshly embodied the principles of the Paris Commune. They were insurrectional bodies of a grassroots democracy – the workers’ councils organizing strikes against the war, sometimes with the aim of controlling their factories; the councils of soldiers who dismissed their officers and replaced them by vote; and the peasant councils that seized the land.

These Soviets played a prominent role in the revolutionary process, but the conviction of the vast majority of the Left was that this process should culminate in a Constituent Assembly for a new Russian Republic. In the main cities of Petrograd and Moscow, where a proletariat of large-scale industry already existed, the Bolsheviks managed to gain the majority in 1917, though not in the vast regions of the Russian countryside, a peasant world dominated by the populists of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, which also sought to gain the majority in a future Constituent Assembly.

It was at that juncture that Lenin launched the slogan “All power to the Soviets,” realizing that the Bolsheviks could dominate the Congress of Soviets more easily than a Constituent Assembly. Against the resistance of a few old Bolsheviks, Lenin and Trotsky decided to take over central power in a daring action of the Petrograd Soviet’s Revolutionary War Committee. They knew that according to the rules of universal suffrage, their party was still a minority throughout Russia, but they expected that the example of the October Revolution would be the signal for revolutions in the advanced countries of Central and Western Europe, and that the center of the World Revolution would quickly move from Moscow to Berlin; thus the importance of the German Revolution, which we will deal with further on.

A new revolutionary government was installed in Russia with Lenin at its head, first in a coalition of Bolsheviks with Left Socialist-Revolutionaries taking the measures that Lenin had promised – to get out of the war and begin distributing the lands of landowners to the peasants. However, the peasant masses still kept faith with the Socialist Revolutionaries, who accordingly won the elections for the Constituent Assembly. To eliminate any danger to the new Soviet power, the decision was taken to dissolve the Constituent Assembly after a single session in January 1918. Lenin’s main argument was that, as a democratic authority, the Soviets were much more democratic than a bourgeois parliamentary assembly would be.

Subsequent developments, however, show that this was not about the power of the Soviets, but about the leading role of the Bolshevik Party. The Soviets were left without any real power, partly because of the intransigent attitude of Lenin himself, but also because of the conditions of a civil war against counterrevolutionary forces. Worker-occupied factories managed by workers’ councils were given over to control by directors appointed from above. Military discipline was reinstated in the Red Army, which included old tsarist officers as indispensable experts. All this culminated in the destruction of the Kronstadt Commune in 1921.

The same year of 1918 also saw the end of Wilhelm II’s empire in Germany. Although most Social Democrats had voted in favor of war credits in 1914, during the course of a war with countless victims and without the prospect of a German victory, a radical opposition – including factory workers’ councils that carried out large strikes against the war starting in 1916 – emerged and gained strength. This “Councilist Movement,” a political force that sought to end the war, also spread to the armed forces and was responsible for the Kaiser’s fall: The sailors’ councils in the city of Kiel refused to obey their officers, thus bringing about the November Revolution of 1918. A councilist movement showing great mobilization ability developed in the factories of the large industrial centers, especially in Berlin. As in Russia, the end of the Empire led to the possibility of a transition to another political system, which could be a representative democracy or a system based on workers’ councils, following the Soviet model. The Social Democratic majority and the trade unions opposed the latter option, which was promoted by the Spartacus League, a group that sprang from left-wing social democracy and fought for a radical revolution based on the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils. In December 1918, however, the first national congress of these councils rejected this option, because it still had a majority of Social Democrats who abhorred the idea of a radical revolution. A great majority of the councilists did not want supreme power for the councils and voted in favor of electing a national assembly, opening the way for the Weimar Republic. The small Spartacist organization tried to correct this course by means of a badly prepared insurrection in January 1919. The troops of the Right easily defeated this attempt, and among the victims of subsequent operations consistently backed by the Social Democrats were Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

Although the way to a new, council-based political system was blocked, this did not put an end to the factory councils or to ideas for restructuring the economy based on councils at all levels, even including a National Council for the Economy. In 1919 and 1920, many debates arose in this regard. The Revolutionary Stewards (Revolutionäre Obleute) movement developed their system of “pure council democracy,” with no chance to put it into practice. Still, various tendencies emerged, even in official Social Democracy, that were aimed at combining representative democracy with democratic economic structures based on the councils and their federations at the regional and national levels, and were even enshrined in the Weimar Constitution. Moreover, invaluable Marxist theorists – among whom the most important was undoubtedly Karl Korsch – distinguished themselves by leaving us writings on the problem of the workers’ councils as superior forms of democracy. Much of Korsch’s work has been translated into Spanish and is available in the previously mentioned editions of “Past and Present.”

All the same, why is it worth going back and studying these old texts, and to what extent may this be useful in the current struggles against certain antidemocratic tendencies in today’s so-termed progressive systems? We have to avoid misunderstandings. By recommending the study of 20th-century revolutions, we are not expecting to find models or recipes in European history so as to imitate them in very different situations in the Latin America of our times. On the contrary, the purpose is to learn from failures and their causes, rather than to imitate spurious examples.

For a broadening of democracy in Latin America, positive conditions as well as specific obstacles certainly exist, and these differ from those found on other continents. There are deep-rooted obstacles in traditions like caudillism that today lead to hyper-presidential phenomena that also crop up in progressive governments. But there are also positive factors: The principle of “Good Living” as it appears in the Constitutions of Ecuador and Bolivia entails a democratic potential because it postulates the strengthening of structures of cooperation and solidarity not yet totally destroyed by the onslaught of capitalism’s destructive forces.

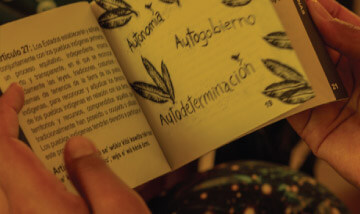

Some universal problems always reappear in the development of democratic movements on different continents and in different historical periods. One of these recurring problems is the relationship between representative democracy, with its achievements and limits, and the forms of a direct, or participatory, democracy in the course of profound social transformations. Many debates in the Constituent Assemblies in Ecuador and Bolivia have focused on this problem in an attempt to combine a formal democracy with forms of self-government by the immediate producers. The struggle to develop indigenous autonomies in Bolivia can be understood as a new manifestation of the validity of the councilist ideal.

As a central part of the Chavezist strategy, the communal councils and communes in Venezuela appear to have a direct relationship with the councilist tradition of a century ago. Their introduction in the very different context of a society deformed by oil rentism poses new problems: There are no historical examples of councils and communes subsidized from above by a central State with inexhaustible resources, as long as oil prices in the worldwide marketplace allow it. Moreover, in the best of cases, these structures of self-government only exist at the grassroots council level, sometimes turning into larger units if communes with productive activities can be formed. This, however, does not solve the most important problem of bringing about a greater democracy, i.e., the control of that democracy by the highest levels of government, including the actions of all its leaders.

If there is no real possibility of correcting the decisions of a supreme leader through open debate, society will likely end up paying a very high price for his or her mistakes and omissions. If councilist structures do not reach to the top, they should at least maintain mechanisms for an adequate control of the executive in a representative democracy, with all its limits and inevitable deformations. In view of the experience with the progressive governments over the last decade, it is advisable to remember an important lesson that Engels took away from the Paris Commune: Victorious revolutionary forces must guard against their own deputies and officials.