Índice

Social scenarios and electoral results in Ecuador

Ecuador’s misfortune presents itself in two distinct ways: first, the surge of both organized and common crime that has rapidly overwhelmed its coastlines, and second, the swift decline in its political representation and state organizational systems, strained by economic hardships and unpredictable electoral outcomes. These issues are intrinsically intertwined. An analysis of the first-round electoral results from the unexpected national election held on August 20, 2023, will help us weave these two aspects into a comprehensive understanding.

The campaign and the election results

On July 23, 2023, an unprecedented tragedy struck when the sitting mayor of one of Ecuador’s largest cities, the port of Manta, was assassinated. Barely a few weeks later, on August 9, another shocking event took place when presidential candidate, Fernando

Villavicencio, was fatally shot upon leaving a rally in Quito[2]. Both Villavicencio and Agustín Intriago, the mayor of Manta, were notable for their vehement opposition to Correismo throughout their political careers, positioning themselves staunchly as anti-Correists.

Considering this severe security crisis, one might have anticipated a significant drop in voter turnout due to heightened fear. However, the elections on August 20 showed no such effect. The voter abstention rate was a mere 17%, the second lowest since 1978. Furthermore, the expression of dissatisfaction with the political system through null and blank votes remained low at 8.8%, also marking the second lowest since 1978. Given the brevity of the campaign season, candidates with deeper pockets or more robust organizational structures—or those with both—had a distinct advantage.

In the sections that follow, we’ll delve deeper into these electoral outcomes, considering the context of the campaign and the prevailing atmosphere of insecurity3. Finally, we’ll reflect on what these developments could signify for Ecuador as it grapples with its double misfortune.

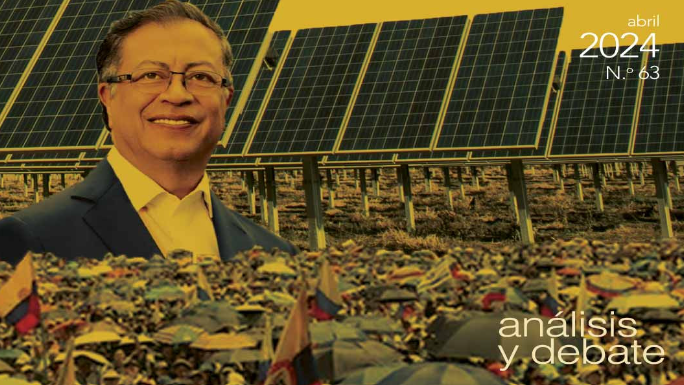

Graph 1. Outcome of the General Presidential Election

Source: National Electoral Council

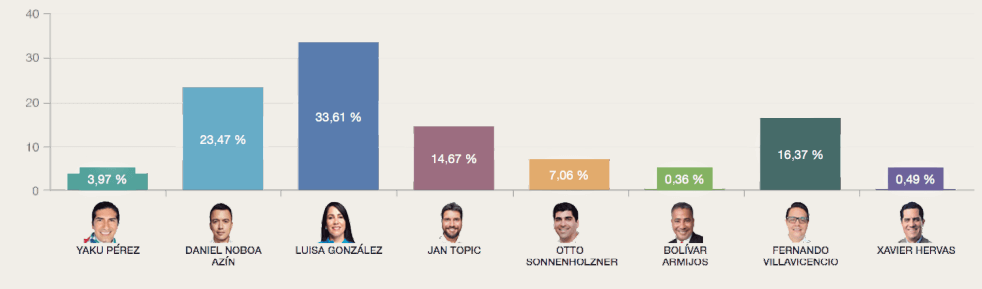

Correísmo secured a nearly identical percentage of votes in the first round of 2023 as they did in 2021, garnering 33.6% of valid votes (as shown in Graph 2.) They achieved a modest increase in assembly members[3][4] and maintained a consistent voter base, with almost the same number of votes for both presidential and national Assembly candidates. Notably, their electoral stronghold displayed a slightly more balanced distribution across regions. While their dominance waned on the Coast, it saw an upswing in the Highlands and Amazon. A striking feature of Correísmo is the steadfastness and consistency of its electorate. Considering its declining vote share since 2013, the recent result can indeed be viewed as a triumph.

But what accounts for this sustained support? Clues can be found in their campaign rhetoric. Central to their messaging was the assertion that “We were better with Correa” and the promise, “We’ll do it again.” In essence, Correísmo’s strategy hinged on the premise that the shortcomings and inertia of subsequent governments would make the electorate nostalgic for what was portrayed as a brighter past.

However, their decision to field a relatively unfamiliar candidate, Luisa González—a prominent conservative hailing from their electoral bastion on the coast, Manabi—didn’t bring them additional votes in that region. Contrarily, Correísmo recorded its poorest performance in its historically loyal province since 2013.

Graph 2. Lenin Moreno 2017, Andrés Arauz 2021, Luisa González 2023 (% of valid votes)

Source: National Electoral Council [5]

The 2023 elections were rife with surprises. Notably, Daniel Noboa and the successor to Fernando Villavicencio, journalist Christian Zurita, captured an impressive 23.4% and 16.3% of valid votes respectively. Villavicencio’s potential as an electoral surprise was hinted at in polls. In my opinion, two factors might explain his popularity:

First, the Correist campaign’s intense emphasis on the achievements of Rafael Correa’s

administration, underscored by his omnipresence in all campaign materials, in a way that far exceeded what happened in 2021, reinforced the feeling that in case of victory it would be Correa who would govern and not González. This perceived overshadowing perhaps stirred and invigorated anti-Correism sentiment, with Villavicencio emerging as its primary beneficiary.

Secondly, Villavicencio championed an aggressive stance against mafias, corruption, and organized crime which are overtaking the State. His promises to govern with an iron fist, coupled with his dynamic persona, created an image of an incorruptible cleaner of the Augean stables. Moreover, Villavicencio went beyond general grievances by explicitly naming individuals he accused, showcasing an unapologetic and defiant stance. Thus, while Jan Topic, backed by the Social Cristiano Party—a traditional representative of coastal business groups—branded himself as the “Ecuadorian Bukele”, a significant portion of voters might have seen parallels between Villavicencio’s approach and the policies of the Salvadoran leader. Additionally, Villavicencio’s familiar public profile, compared to the relatively unknown Topic, weighed in his favor. His assassination further swayed public sentiment, yielding a surge in support for his slate.

Daniel Noboa’s impressive electoral showing is harder to decode. As the son of banana magnate Álvaro Noboa, who has vied for the presidency five times in the past 25 years, Daniel made a mark during the August 13 presidential debate. Not only did he provide direct answers, but he also adeptly tackled a range of issues. Unlike many of his peers, he didn’t narrow his focus to just security, demonstrating a well-rounded performance across the board. During his campaign, Noboa consistently showcased a platform centered on the economy, employment, and social policy. Despite having a vice president with strong neoliberal and anti-abortion views, Noboa managed to strike a more balanced and nuanced stance on campaign topics than most of his competitors. His adept performance in the presidential debate bolstered his image as an effective administrator, a boost similarly experienced by Xavier Hervas in 2021. Noboa, with seemingly bottomless personal funds, traveled across the nation, distributing aid such as medical services, food, seeds, and even practical campaign materials like clothing[6]. The question then arises: what accounts for his unexpected surge in votes?

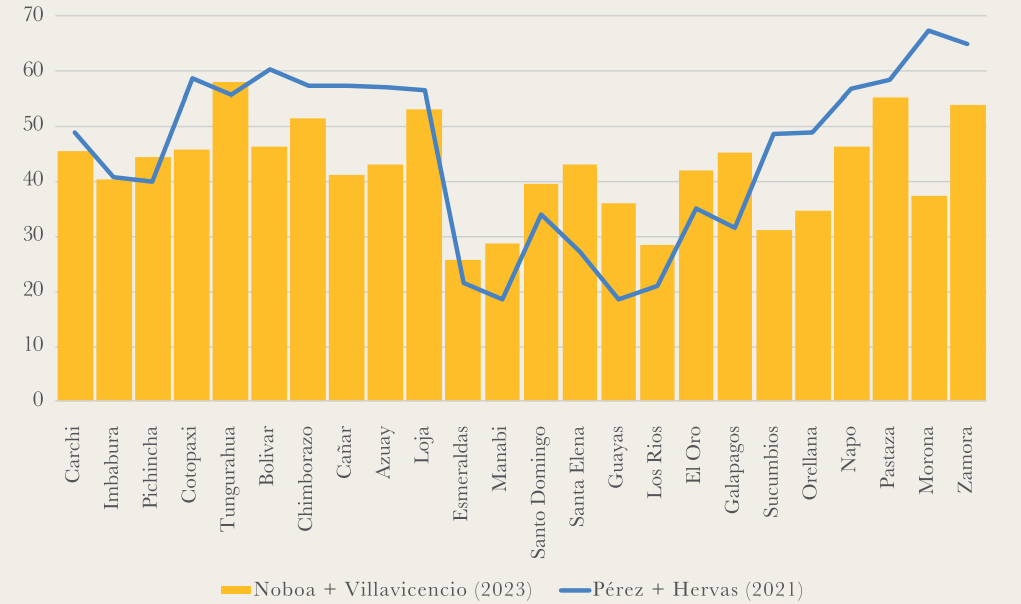

Comparing 2021 and 2023, electoral data (Graph 3) [7] reveals a substantial voter migration from Yaku Pérez and Xavier Hervas to Noboa and the Villavicencio/Zurita ticket. Pérez, the indigenous movement representative, and Hervas, of the social democratic party Izquierda Democrática, historically leaned towards center-left and anti-Correism positions. Zurita’s voter base incorporated an additional dimension. The assassination of Villavicencio initially seemed to bolster Jan Topic, especially in coastal regions. However, as time progressed, momentum shifted towards Villavicencio’s successor. Ultimately, his tragic passing and the subsequent outpouring of public empathy propelled his ticket to secure 16% of votes. Notably, neither of the first round’s front-runners, Luisa González or Daniel Noboa, prioritized security in their campaigns, instead emphasizing a broader socio-economic narrative.

Graph 3. Vote for Pérez+Hervas (2021) and Noboa+Villavicencio (2023) (% valid)

Source: National Electoral Council [8]

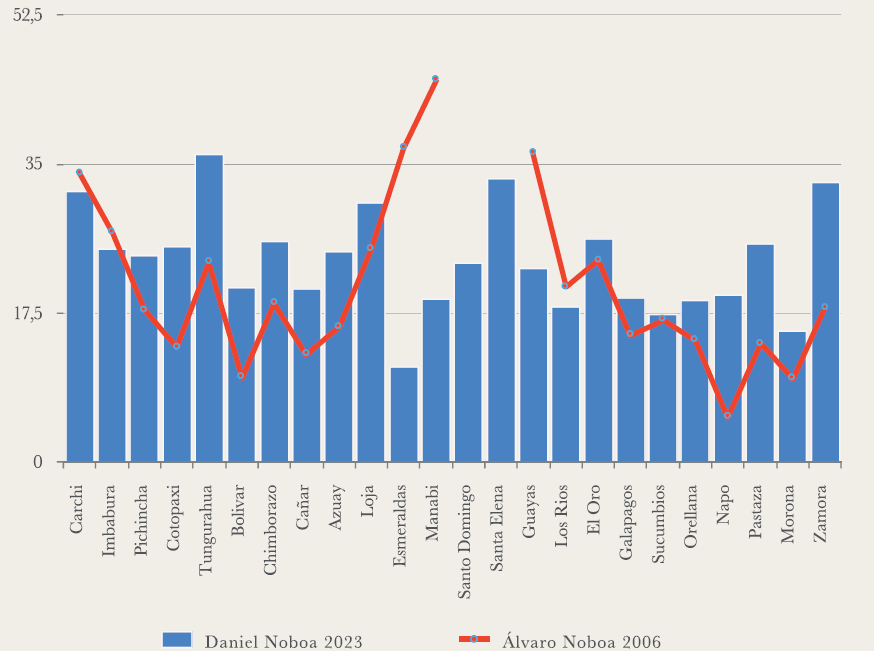

Within Daniel Noboa’s voter base, besides the highlands’ support for Pérez and Hervas, there’s a notable shift of his father’s followers – the banana magnate, Álvaro Noboa. In post-first-round interviews, Daniel Noboa drew parallels between the 2006 vote for Rafael Correa and his own electoral base. However, upon closer examination, Noboa’s voting distribution seems to resemble a blend of his father’s 2006 candidacy and the 2021 support for Yaku Pérez and Xavier Hervas (as illustrated in graph 4). This overlap offers the best explanation for his robust vote tallies in regions like Guayas and Manabi.

Interestingly, Noboa struggled to siphon votes from Correísmo in Esmeraldas, an area with a significant Afro-Ecuadorian population that had previously been ardent supporters of the senior Noboa. The indigenous regions of the Amazon and the central Highlands have historically been elusive for Álvaro Noboa, just as they have been for Rafael Correa since 2006. Yet, the younger Noboa seems to have not only tapped into this demographic but also inherited their support.

Graph 4. Valid votes Á. Noboa 2006 – D. Noboa 2023

Source: National Electoral Council[9]

The dramatic decline in support for Yaku Pérez and Xavier Hervas in the elections calls for a deeper analysis. In 2021, their combined votes were primarily from the highlands, traditionally aligned with the center-left, and also from the anti-correist faction, which had previously supported Guillermo Lasso in 2017. These voters were looking to break away from the stark polarization between Correismo and the business-centric

right-wing factions.

Both Pérez and Hervas made a critical error in assuming that their 2021 votes were purely based on their personal appeal. Hervas, for instance, felt that he had captured the youth’s attention through his presence on TikTok. Yet, a closer look at the geographical and social distribution of his 2021 votes suggests it overlapped heavily with areas traditionally supportive of the Izquierda Democrática (ID) party. Even if Hervas did engage the young TikTok audience, it wasn’t random. They were more inclined to listen where remnants of ID influence lingered.

As for, Yaku Pérez, he made the political declaration that his voter’s base was a personal asset when in May 2021 he withdrew from Pachakutik, the electoral movement associated with the indigenous community, effectively leaving Conaie in the control of his rivals. Initially, during the campaign, it appeared Pérez might retain his 2021 vote share since he was the sole representative of the center-left faction. But this campaign and its leadership forgot an essential factor: Pérez’s appeal in 2021 was largely due to his ability to resonate with the anti-correism sentiments of the economically downtrodden and rural dwellers of the Highlands and Amazon. His message then was a balm for the frustrations of those most marginalized by an unforgiving economy and indifferent governments, a sentiment that exploded in the popular uprising of October 2019. His 2021 campaign had a spiritual tone, focusing on harmony and unity, which seemed a fitting response to the previous year’s uprising.

However, in the 2023 campaign, divorced from the movement and its legacy (which he scarcely referenced), his message of unity and spiritual peace seemed out of place. The times demanded leaders with vigor and determination to address a rapidly deteriorating socio-economic landscape.

Misfortune in perspective

The Ecuadorian electorate, particularly the anti-Correist faction, has ardently pursued a “third option” as an alternative to the persistent polarization between Correism and the business right. This quest has now gravitated towards more conservative choices. This development is a poignant setback for Ecuador’s grassroots movements, which have been historically steered by the formidable indigenous community.

At the heart of this shift lies the transformation of dire economic hardships into an unparalleled public security crisis. However, the leadership of the popular movement also bears responsibility. Amid a convoluted and challenging landscape, their internal divisions, ambitions, and contrasting personalities have come to the forefront, inevitably exacting a substantial political price.

The prospects for rebuilding left-wing political alternatives are deeply interwoven with the significant outcomes of the public consultation on protecting Yasuni and the Andean Chocó from oil and mining extractivism. In these historic outcomes, stemming from the first two official public consultations achieved through citizen initiative, signature collection, grassroots organizing, and countless legal measures, lies a legacy of public trust, grassroots environmentalism, and a desire to transform the productive matrix. This reminds us that public sentiments and choices can be contradictory, yet there are anchors to which we can cling in the pursuit of a better society.

However, the apparent paradox between the environmental vote and the electorate’s rebuke of disreputable elites — who stoked fear to overturn the public’s decision, coupled with backing electoral choices at odds with such aspirations — is a dilemma that will need addressing in the coming years.

The second round appears initially to favor Daniel Noboa over Correísmo; however, the campaign might be extended and potentially tumultuous. While in the initial rounds, voters often settle for what they perceive as the lesser evil, by the time the second round comes, fear and unease often tip the scales. Voting against, rather than for, becomes the norm. The Correist approach of prominently featuring Rafael Correa has reinvigorated anti-Correism, whereas much of the skepticism surrounding Daniel Noboa stems from his father’s reputation. This might explain why the younger Noboa often leans into the support of his mother, a physician who joins him on his tours. Even though both candidates are relatively new to the national political scene, Luisa González’s campaign appears to rely more heavily on her mentor than Noboa’s does on his father.

The ensuing year and a half post-election will scarcely allow for any significant structural reform; it will be a brief period geared towards reconstructing a stable majority. The primary focus of the new administration will be to capitalize on the political fragmentation and the prevailing public distrust. Regardless of the victor, any vision for a promising future would necessitate a fervent drive towards investments in infrastructure, public works, and social expenditures. This approach alone may foster a parliamentary majority and potentially end the epoch of ephemeral parties and candidates — those that momentarily shimmer during the electoral seasons, only to swiftly vanish in the bleak winter of fiscal austerity. Such an agenda holds the potential to be the starting point for the critical and timely response to criminal violence and organized crime. Within the confines of this brief endeavor, heavily reliant on adept public fund management, it will be incumbent upon the popular movements to rejuvenate their strategic insight and craft a foundational unity.

[1] Professor at the Simón Bolívar Andean University and activist of the Commission on Experience, Faith and Politics.

[2] No details of the investigation into the murder of Fernando Villavicencio are known. His closest relatives, and Villavicencio himself, days before his death, pointed to alias Fito, head of the Choneros, linked to the Sinaloa Cartel, from whom he had reportedly received several threats.

[3] Material from three 2023 published interviews conducted with me has been incorporated into this analysis:

Stefanoni, P. (2023.) Ecuador, on the edge of the precipice. Interview with Pablo Ospina and Franklin Ramírez. Nueva Sociedad, August. https://www.nuso.org/articulo/ecuador-urgente/; New Society. (2023.) Elections in Ecuador.

Balance and perspectives (Opinions of Pablo Ospina, Augusto Barrera and Paulina Recalde.) Nueva Sociedad,

August. https://www.nuso.org/articulo/ecuador-elecciones-2023/; Ravier-Regnat, S. (2023.) Interview. Elections en Équateur: héritiére de “Luisa González suscite beaucoup de rejet” (Interview with Pablo Ospina.) Libération, August 22. https://bit.ly/468hhwk

[4] 52 out of 137 if we take into account the assembly members elections abroad, where the elections are likely to be repeated; that is, 3 more than in 2021.

[5] 2017, 2021 and 2023 election results, Available at https://www.cne.gob.ec/

[6] See, for example, an April 29, 2023 photograph of Daniel Noboa delivering food aid in González, M. (2023.) The five factors that took Daniel Noboa to the second round. Primicias, August 22. https://www.primicias.ec/noticias/elecciones-presidenciales-2023/daniel-noboa-factores-segunda-vuelta/

[7] According to a paper by Viteri, R. and Naranjo, S. (2023) titled “Analyzing the First-Round Vote Transfer from 2021 to 2023: A Mathematical Perspective,” published in GK on August 24, approximately 60% of the votes cast for Xavier Hervas and Yaku Pérez were transferred to Noboa and Villavicencio. https://gk.city/2023/08/24/transferencia-de-votos-2021-2023-primera-vuelta-explicacion-matematica/

It is possible that a cantonal vote analysis and comparison with 2021 will increase the estimate. See Noboa, A. (2023.) 44 cantons, especially on the Coast, are the most faithful to Correismo. Primicias, August 22. https://www.primicias.ec/noticias/elecciones-presidenciales-2023/comparacion-resultados-cantones-luisa-gonzalez-daniel-noboa/

[8] 2017, 2021 and 2023 election results. Available at https://www.cne.gob.ec/

[9] 2023 election results. Available at https://www.cne.gob.ec/ ; Supreme Electoral Tribunal, Electoral results, first round, October 2006.